How many maqams are there?

March 26, 2008 2:24 pm Arabic Music, Music TheoryThis question is not only one that a new comer to Arabic music would ask. It is also valid when asked by an Arabic music theorist. There are three main reasons for that:

- Simplification of the definition of maqam therefore not recognizing some of the characteristics that distinguish different maqams sharing the same scale. As a result, many maqams that share the a scale are now considered one maqam.

- Maqams that are no longer in use are omitted from theory books.

- Not recognizing intonation details rendering several different maqams as identical.

Let us examine each category and study some examples.

Simplification of the definition of maqam

There is a general tendency to teach all or, at least, some maqams simply as scales. Not only that, but there is a general tendency to theorize that each maqam has one scale associated with it, not more. That is not in keeping with the spirit of maqam based music. Here are a few examples of this trend to simplify.

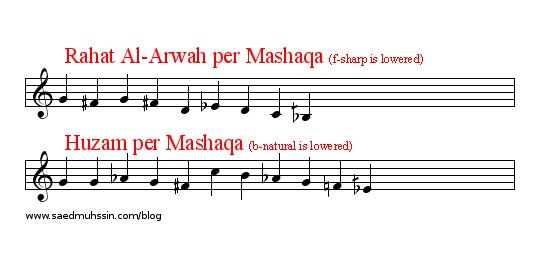

- Ignoring Sayr (characteritic melodic movement) in a maqam. Some maqams have identical intervals but are different in their melodic progression (starting region, emphasis on specific regions or pitches, cadences, etc..) For example, let us compare the two maqams Huzam and Rahat Al-Arwah. In the past, the maqams were considered different because of a different melodic progression (see example). Traditionally Rahat Al-Arwah had always been recognized to have a B half flat tonic while Huzam had a tonic of E half flat. But they are not merely two transpositions of the same maqam. Notice that both Mashaqah and other theorists have variations on the definition of huzam. But in none of those variations is Huzam identical in Sayr to Rahat Al-Arwah according to the “old” theory. Therefore teaching Rahat Al-Arwah and Huzam are merely different names of the same maqam when transposed to different keys ignores the real difference between them (Arabic music, after all, doesn’t recognize maqams transposed to different keys as different maqams by virtue of the transposition) which is the Sayr. It is worth noting here that Sayr should be regarded as a general architecture that shows regions visited and/or emphasized and directions of motion in specific situations as opposed to exact phrases to be played.

-

Another example of the simplification of maqam definition is maqam Farah-Fazah (Ferahfeza in Turkish). I agree with the view that this is an Ottoman maqam. In fact, some of my Turkish informants commented that this is a maqam that was conceived by Tanburi Cemil (Jamil) Bey. I couldn’t find any documentation of this. However, I don’t read Turkish, and have little access to Turkish sources (I rely on the generosity of Turkish friends). Since it would be reckless to discredit the claim that this maqam was conceived by Tanburi Cemil without consulting with the Turkish literature, I would just leave it here, and hope that someday someone would find this post and give some information. At any rate the problem with Farah-Fazah is not who first conceived of it.

In its Ottoman definition (as per “Turk Musikisi Nazariyati ve Usulleri”, by Kudum Velveleleri) Farah-Fazah is a compound maqam: a maqam associated with the scales of more than one maqam. Per Velveleleri, maqam Farah-Fazah is a descending maqam that contains the maqams of Busalik on G, Ajam on B-Flat, and Bayati on D. Turkish classic compositions in this maqam follow this recipe. Salim Al-Hilu’s work on Arabic Music Theory (Al-Musiqa Al-Nathariyya) recognizes the Ajam aspect of it. More modern teachings simply regard it as Nahawand from G. Again regarding it as a different name for the same maqam only due to transposition and not as a maqam of a different nature. Notice also that in its Turkish definition, the maqam is not based on Nahawand from G, but on Busalik from G. Busalik is another maqam that in modern Arabic theory was lumped into the Nahawand conglomerate as another name for Nahawand on D (as opposed to a maqam which shares a scale but is different in Sayr).

- Maqam Najdi Sika, is no longer mentioned in modern literature because it is also considered to be identical to Sika. The difference between the two is that Najdi Sika emphasizes the upper register, and resolves to the tonic only in cadences or ends of movements. Since the distinction of emphasis areas was dropped from maqam definition, this is no longer its own maqam.

Maqams that are no longer in use

A few examples mentioned in Mashaqah that I haven’t encountered in modern literature and know of no compositions that use them: Awj Khurasan, Shurouqi, Maa-Rana.

Ignoring intonation details which eliminate certain maqams

Case in point. Maqam Sika Rumi which I hadn’t heard of until the summer of 2006 when Prof. Jihad Racy introduced his composition Samai Sika Rumi. This maqam is similar to Sika except for the fact that it’s tonic is sharper than the traditional E half flat tonic of Sika. Ignoring the intonation difference between the two tonics (and possibly some Sayr details) would render Sika Rumi identical to Sika. The sound of the two maqams, by the way, is extremely different. Sika Rumi is the most ethereal sounding maqam I know of.

So how many maqams are there? Between fourty and four hundred (or more) depending on how you look at it..